Anarchy Examples: Historical Precedents of Stateless Societies

Step beyond conventional history and discover compelling examples of societies that thrived without the centralized control of a state. This page delves into various historical and contemporary case studies, demonstrating that complex social order, legal systems, and vibrant communities can emerge and endure through voluntary association and decentralized governance. Prepare to challenge your assumptions about what's possible when individuals are truly free.

Jericho

11,000 B.C.E. - 9,000 B.C.E.

The early settlement of Jericho, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, provides a fascinating glimpse into pre-state social organization. During its early Neolithic phases, particularly the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A and B periods, archaeological evidence suggests a society that lacked the hallmarks of a centralized, coercive state. While walls were built, likely for defense against external threats or to manage resources, there is little indication of a hierarchical political structure, a ruling elite, or a standing army enforcing laws.

Decisions regarding community projects, resource allocation, and conflict resolution appear to have been made communally or through informal, decentralized mechanisms, demonstrating a capacity for complex social organization without the need for a dominating state apparatus.

Dates

11,000 B.C.E. - 9,000 B.C.E. This period represents Jericho's early, pre-state phases where social organization thrived without centralized authority.

Çatalhöyük

7500 B.C. - 6400 B.C.

The Neolithic settlement of Çatalhöyük in Anatolia is renowned for its unique urban layout and social structure, which challenges conventional understandings of early civilization. For over a millennium, its inhabitants lived in closely packed, interconnected dwellings with no discernible streets or public buildings.

Crucially, archaeological excavations have revealed a striking lack of evidence for social stratification, such as differences in housing size, burial goods, or monumental architecture dedicated to a ruler or deity. There are no signs of a central authority, a ruling class, or specialized institutions for governance or law enforcement. Instead, decisions and social order appear to have been maintained through horizontal relationships, shared cultural norms, and localized family or clan structures, highlighting a complex and thriving society that operated without the presence of a coercive state.

Dates

7500 B.C.E. - 6400 B.C.E. These dates mark the primary Neolithic occupation of the eastern mound, during which Çatalhöyük exhibited its notable stateless characteristics.

Xeer Legal system

Somalia

600 C.E. - 1600 C.E.

For centuries, much of Somali society has operated under the Xeer legal system, a customary law tradition that exemplifies a decentralized, stateless form of governance. Rather than relying on a central government or judiciary, Xeer is a complex body of unwritten laws, agreements, and social contracts negotiated and enforced by elders, clan councils, and ad hoc assemblies. Disputes are resolved through mediation, compensation, and negotiation, with strong social pressures and clan honor acting as primary enforcement mechanisms.

This system operates without prisons, police forces, or a formalized state bureaucracy, demonstrating how a society can maintain order, resolve conflicts, and regulate social interactions through voluntary agreements and community-based enforcement, underscoring a profound absence of a centralized, coercive state.

Dates

600 C.E. - 1600 C.E. This range represents a significant historical period of Xeer's prominent use, though its influence and active application continue in many parts of Somalia today.

Brehon Law

600 C.E. - 1600 C.E.

Brehon Law, the indigenous legal system of Ireland before the Norman invasion, provides a compelling historical example of a highly sophisticated legal framework operating without a centralized state. Rather than a king or government dictating laws, Brehon Law was administered by brehons (jurists) who were highly respected legal experts. These brehons did not make law but interpreted and applied a vast body of customary laws, precedents, and legal principles.

Enforcement was largely decentralized, relying on social pressure, reputation, and the payment of fines or restitution. There was no standing army or police force to compel compliance; instead, a person's honor and the collective pressure of their kin group ensured adherence. This system fostered a society where justice was delivered through a highly developed legal scholarship and community accountability, rather than through the coercive power of a state.

Dates

600 C.E. - 1600 C.E. This period encompasses the full development and widespread application of Brehon Law as a formalized system before its suppression by external powers.

Icelandic Commonwealth

930 C.E. - 1262 C.E.

The Icelandic Commonwealth stands as a remarkable historical example of a society that functioned for over four centuries without a centralized executive authority or a standing army. Conventionally dated from its formal beginning in 930 C.E. with the establishment of the Althing – though its settlement began earlier around 874 C.E. – the Commonwealth thrived on decentralized principles. Power was distributed among chieftains (goðar) who held both religious and legal influence, but their authority was derived solely from the voluntary allegiance of their followers, not from a coercive state apparatus. The Althing, a national assembly, served as a legislative and judicial body where laws were debated and disputes resolved, yet it lacked any executive power to enforce its rulings.

Enforcement relied primarily on private legal action, arbitration, and the social pressure of the community. Its unique existence came to an end around 1262-1264 C.E. with the "Old Covenant" (Gamli sáttmáli), when Icelanders pledged allegiance to the Norwegian king, followed by the adoption of the Jónsbók law code in 1281 C.E. This period in Icelandic history is often cited as a prime example of a functioning anarchist society, demonstrating how complex social order could be maintained through decentralized governance, voluntary association, and an elaborate legal system without the presence of a coercive state.

Dates

930 C.E. - 1262 C.E. This precise range covers the formal establishment of the Althing and the duration of the Commonwealth as a distinct, stateless political entity before its subjugation.

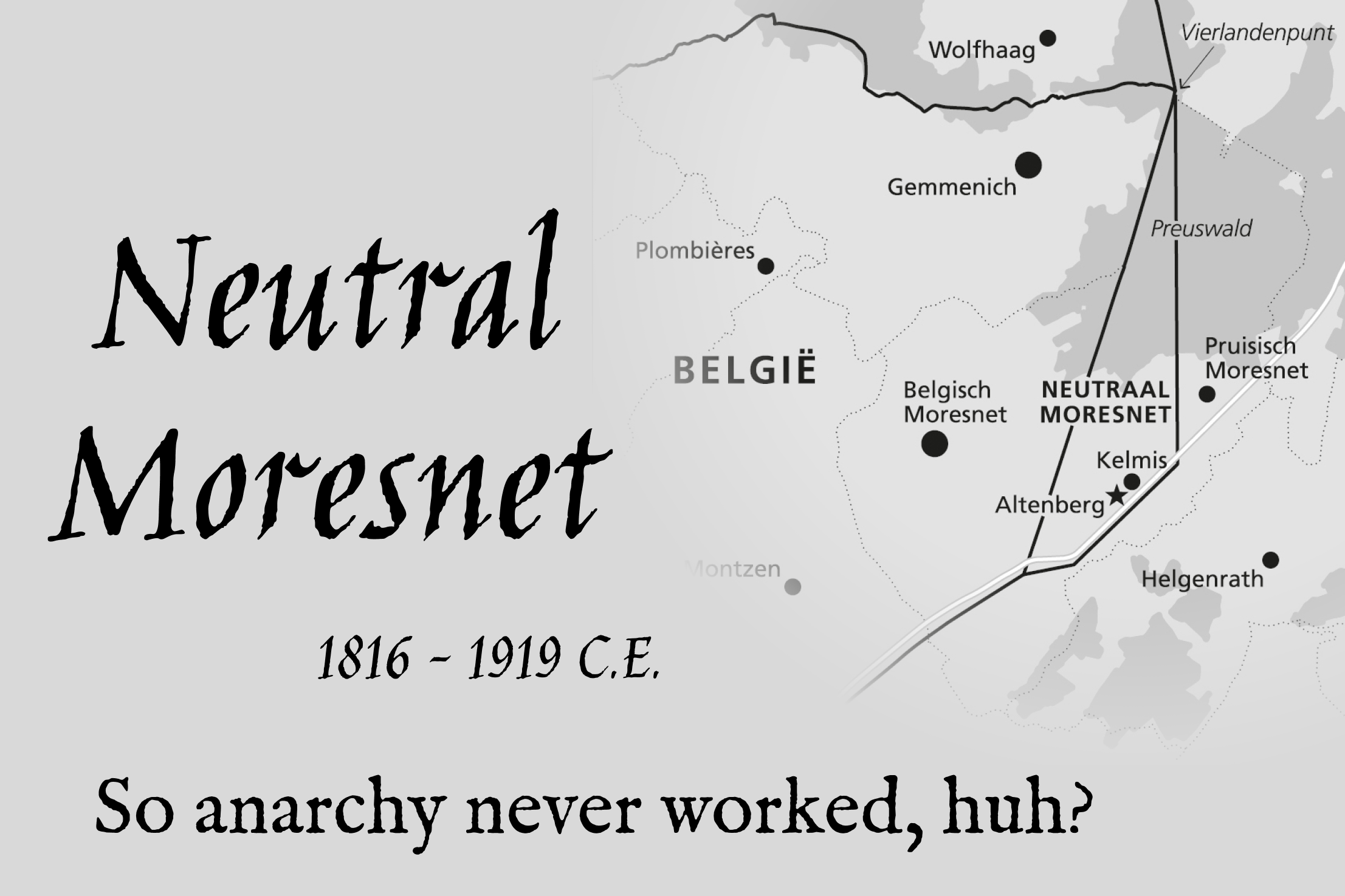

Neutral Moresnet

1816 C.E. - 1919 C.E.

Neutral Moresnet, a tiny condominium administered jointly by the Netherlands (and later Belgium) and Prussia (and later Germany), existed for over a century with a remarkably decentralized and largely self-governing character. Formed due to a border dispute, neither larger power fully asserted its control, leading to a unique situation where the local population largely managed its own affairs. While there were nominal administrators from the co-ruling powers, the community developed a strong sense of autonomy, with little direct interference or coercive state presence. Local committees, communal decision-making, and a pragmatic approach to governance meant that for decades, this small territory operated with minimal centralized authority, showcasing how a community can thrive and maintain order with a significant absence of a formal, powerful state apparatus, particularly notable for the rise of Esperanto as a potential official language in the early 20th century, further highlighting its unique, non-state character.

Dates

1816 C.E. - 1919 C.E. This period marks the establishment of Neutral Moresnet's unique status until its formal dissolution by the Treaty of Versailles.